Stolpersteine – Stones for the Disappeared

Literally “stones one is meant to stumble over (with one’s eyes).” These are special cobblestones with a brass surface, set into the pavement in front of the former homes of Holocaust victims and others persecuted by the Nazi regime.

Stolpersteine jsou projektem německého umělce Guntera Demniga. První kámen byl položen 16. prosince 1992 před radnicí v Kolíně nad Rýnem. Myšlenka se postupně rozšířila do celé Evropy a nové kameny se pokládají každým rokem.

Stolpersteine have been present in the Czech Republic since 2008. At least one stone has already been placed in over ten cities across the country. In Prague alone, more than 800 Stolpersteine have been installed. You can find more about the project at: www.stolpersteinecz.cz.

The Project is being implemented in 2025 with financial support from the Office of the Government of the Czech Republic. The outputs of the Project do not represent the views of the Office of the Government of the Czech Republic, and the Office bears no responsibility for the use of the information contained in these outputs.

Video of the stone-laying ceremony in 2024:

The Righteous Among the Nations

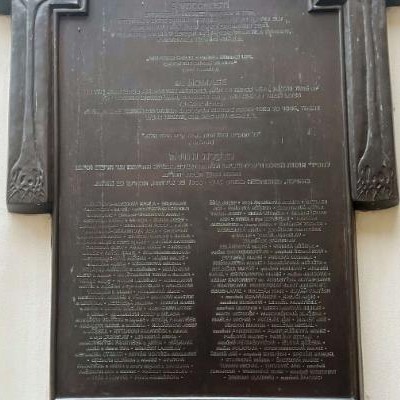

The Righteous Among the Nations award honors those Czech citizens who risked their lives during the Holocaust to save others. The original memorial plaque in the courtyard of the Pinkas Synagogue bears the names of 115 of these individuals. In reality, however, there were more – and we launched a fundraiser to restore the memorial and add the missing names. The fundraiser was successful, and we sincerely thank all the donors..

The ceremonial unveiling of the memorial plaque will take place on September 18, 2025, at 5:00 PM, in the presence of the plaque’s designers.

Unto the Third Generation

Helena Klímová, psychotherapist, writer, and Charter 77 signatory

illustrative photo: Nick Bolton

It’s early afternoon. I open my office, curious about the new client who had reached out to me. A university student arrives—about the age of my granddaughters. Large brown eyes, upright posture, clothes that suit her frame, a calm voice with a well-balanced, low tone, a firm handshake—the first impression is pleasant. She sits down in the armchair and begins to speak. As if nothing were wrong—except for a recurring nightmare that haunts her.

She’s afraid to fall asleep—it’s always the same dream. She has to run, desperately fast; someone is chasing her; she’s terrified. She runs, gasping for breath—they want to kill her! She wakes up drenched in sweat, unable to fall back asleep... shaken until morning. But why does she keep having this dream over and over again? While awake, she has no worries—no trouble at home, no issues at school, no problems with boys...

read more

I listen and ask questions… No, she didn’t witness parental fights, nor was she in daycare at an early age. No childhood bullying, no trauma… she gets along well with her classmates… No, even her mother wasn’t in daycare... And that’s what’s so strange, the girl circles back to her dreams. Each time, along with the terror, she also feels a sense of wonder—why are they chasing her? She didn’t do anything wrong…

And as I listen to her dream, a memory suddenly surfaces: I’m a little girl in our apartment building in Smíchov, running down the stairs. The neighbor’s children—German children—are chasing me, grabbing at me, tearing off my school satchel, shouting “blöde Jude,” kicking me…

“And what about your grandparents?” I ask the client. “Your grandfather and grandmother?”

The girl looks astonished. “Well, that was ages ago, during the war… they were Jews, persecuted, in a concentration camp and all that… You think that’s where my nightmares come from?”

Another example: a colleague, a psychiatrist, refers one of his patients to me—a university student struggling with depression. I invite him in and immediately notice how striking he is, both at first glance and first touch. He arrives wearing jeans so torn and worn out that they surpass even the boldest street fashion, and when we shake hands, his feels injured... As he begins to speak, I listen to the story of his self-harm.

But no, self-harm isn’t the intention, the student says—the intention is to triumph over danger. And when you’re riding a bike downhill through forest ruts, or skiing headlong, or speeding on a motorcycle, injuries sometimes happen... but you always heal from the scrapes and broken bones in the end. And each time—surviving again—that’s what it’s all about, survival! Proving it to yourself!

This young man sees the connection quite openly: his mother has suffered all her life from various physical pains for which medicine offers no clear explanation. As if someone were causing her injuries—but of course, that’s not the case. And her mother, his grandmother, the young man says, was a hidden child during the war. A farmer hid her—in a stable among horses—and the little girl had to be constantly careful not to be struck by their hooves…

The young man is intelligent; the logical connection between the fates of the three generations seems clear to him. As if, in some delayed way, he were doing something on behalf of his mother—or rather his grandmother. As if he were overcoming the dangers and risks they once faced—but risks he first has to create for himself... But isn’t that explanation too simple, too bold? And then—why is he still plagued by depression?

We don’t have all the answers readily at hand, but we have hope that therapy will gradually help relieve the symptoms. I invite the young man to join a therapy group for descendants of Holocaust survivors.

We are careful not to see the connection between the persecution of parents and grandparents and the worries or suffering of later generations as too simple or one-dimensional. Nevertheless, the link between generational fates is supported by biological arguments as well—epigenetic changes, alterations in inherited information. The descendants of traumatized people (and even so-called lower animals) carry in their bodily memory a message about potential danger—a message meant to protect them.

And yet that message—if we can understand it this way—causes our clients all kinds of pain, distress, anxiety, and sleeplessness. What we aim to offer them in therapy is not just an intellectual explanation or rational understanding. Reason alone is not enough. What therapy offers is also something that’s very difficult to explain purely through reason. Therapy provides an experience—sometimes a repeated one—one that contains a corrective emotional encounter: a kind of forgiveness, both of oneself and of fate, a sense of self-acceptance, and joy in one’s being among others. This does not happen through intellectual insight alone; the transformation occurs in a way similar to how the original wound was formed—through the lived experience of the whole being, including the body, the senses, and ideally through repeated emotional encounters.

The original wound was shaped not only by heredity but also by unconscious communication—by the language of the body: how the father silently hid his tattoo, how the mother suddenly sighed and fell silent at certain words, how some topics were censored in family conversations, how voices were lowered and curtains drawn at home so as not to reveal something about ourselves… but what exactly?

Children initially absorb such messages as part of the natural order of the world. Only later do they become aware of their extraordinary nature—through intellectual realization. But the part taken in during childhood, through the senses, remains untouched by reason. The body attempts to expel it, as it would any harmful element, yet lacks the tools, the language, the means to rid itself of it—except through illness or disorder.

That’s when psychotherapy seeks out and offers such a language. First and foremost, the royal road of dream interpretation, but also drawing, painting with group interpretation, role-play in which individuals empathize with each other’s positions and, in doing so, better discover their own, and group dialogue… Therapy may begin with rational insight, but it proceeds along sensory paths—reaching into what lies beyond conscious awareness. It often employs the language of the body, thereby reconnecting with events from childhood, with a time that came before reason.

Trauma reaches across generations—into the third and fourth—touching even those who are not yet born. We wish for these future generations health and release from this cycle. There is hope—but it depends on recognizing the particular needs of those who carry such inherited wounds, and above all, on the provision of therapeutic care.

Scarred by the Holocaust

Zuzana Peterová, psychotherapist

illustrative photo: Anna Keibalo

„Sama jsem naštěstí válku neprožila, ale pořád myslím na slova mé babičky, která byla v koncentračním táboře Osvětim. Vyprávěla mi, co pro ni znamená slovo „transport“, nebo „kufr“, do kterého si všichni Židé museli zabalit to nejnutnější, než odešli do lágrů.“

And how she still can’t even look at ordinary cooking fat—margarine, the wartime substitute for butter. It was, after all, food from the time of war. She also spoke about how, to this day, she can’t bear waiting for someone who’s late—because that’s exactly what she did, for hours and hours, days and weeks, waiting for all her siblings, her parents, many other relatives and friends. In vain. They never returned.

read more

These are the words of many of my clients from the so-called second and third generation, who listened to the stories of their family members. And even though they did not experience those hardships themselves, the stories planted deep seeds of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty in their hearts and souls.

As a psychotherapist, I often meet people in distress who, for various reasons, visit doctors—only to be told, with a tone of reproach, that they have no reason to think about the war or fear the annihilation of their families, because “the Holocaust was so long ago, everyone has forgotten it by now…”

They have not forgotten. The descendants of Holocaust survivors are born with a deep-seated fear of violence, with mistrust toward unfamiliar people and situations. It is only through great strength of will that many of them manage to show no outward signs of this throughout most of their lives. But those who are allowed a closer, deeper look into their aching hearts and souls can feel and see just how profound the inherited fear of survival truly is—how great the uncertainty around stable emotional bonds, how strong the anxiety about meeting difficult challenges—just to “live up” to what a superior expects of them.

Low self-confidence, pervasive fear, and deep mistrust—these are the three constants that accompany the second and third generation of survivors as an indestructible legacy. And while willpower may help mask these emotions more skillfully, it cannot erase them.